Building an office is not just about workspace design. The latest and greatest commercial buildings combine world-leading architecture and sustainability with a holistic ethos of health and wellbeing. And that can lead to real benefits for employee happiness – and productivity

The conversation around, about and inside corporate architecture is changing as fast as the landscape of our global cities. Not so long ago, solar panels incorporated into a building seemed fairly radical; now, they seem as if they are entry-level in the sustainability or green and wellness debate.

In 2018, this debate involves a plethora of detail, from how the color temperature of light affects an employee’s productivity to the quantifiable market value a sustainable building initiative represents to a company’s brand. And the standards for these details are being set by a variety of initiatives, from organizations such as the International WELL Building Institute (IWBI) and the US Green Building Council (USGBC).

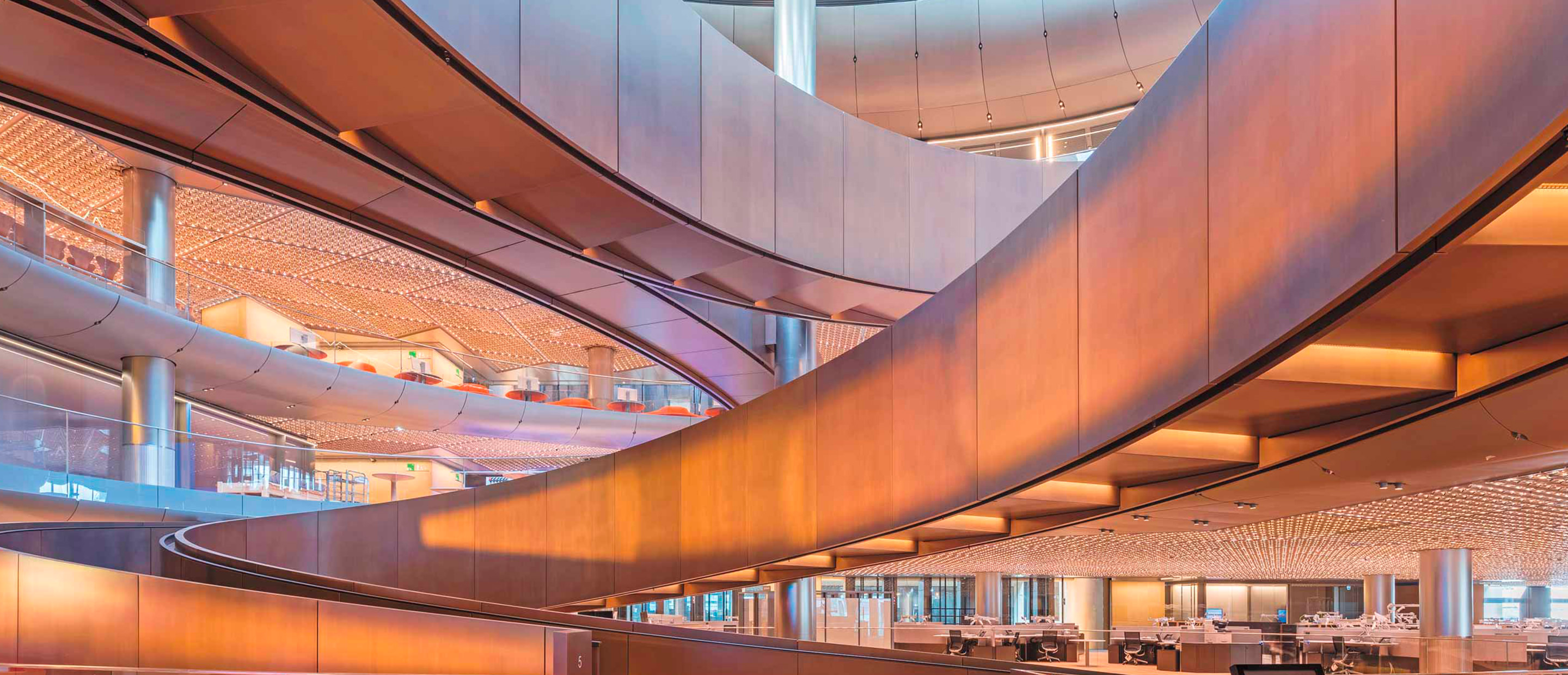

When Bloomberg’s new European headquarters, designed by Foster + Partners, opened in the City of London in 2017, the building attracted phenomenal attention for its sustainability – urban planning in line with the personal philosophy of the media empire’s Chief Executive Officer Michael Bloomberg, and the Bloomberg Philanthropies environment program. The building achieved a 98.5 percent score – the highest to date for an office development of such a scale – when assessed using the green certification scheme BREEAM (Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Method). If the architecture itself lacks the height and visual impact of many other recent additions to the city’s skyline, its narrative has an impact far beyond the immediacy of Instagram.

Three years before the Bloomberg building opened for business, London-based PLP Architecture had unveiled The Edge in the Zuidas financial district of Amsterdam. It was the result of nine years’ work with client Deloitte, the building’s main tenant, and the developer and owner OVG, the Dutch real estate company. The 40,000 square meter (430,000 square foot) smart building won the 2016 BREEAM Office New Construction Award. In terms of aesthetics, The Edge is a dynamic new landmark, while representing an exciting and innovative paradigm of how architecture and sustainability relate to business.

“The development was initiated by Deloitte when the company was going through a transition into the digital age,” says Ron Bakker, a partner at PLP Architecture. “They were wondering how they would advise clients about doing business in the future, and thought The Edge was the future of office space. Deloitte signed a 15-year lease with OVG, which meant that in terms of the sustainable features of the project, anything Deloitte added to the building’s design would pay back on OVG’s investment in 10 years. When OVG sold the building to [German real estate investor] Deka, we know they did well out of the deal. It represented a way of investing – there was value to the sustainability.”

The experience of Deloitte and OVG should become typical in the future. Research by the World Business Council for Sustainable Development, an organization of more than 200 businesses, says the general perception that building green adds around 17 percent to construction costs is far from accurate; in fact, it adds less than 2 percent to costs while increasing the value of the resulting building by 6 percent. And as the Deloitte project has shown, the value sustainability can add to a brand goes way beyond that.

When construction group Skanska moved into its new-build global headquarters, Entré Lindhagen, in Stockholm, Sweden, in 2014, it planted a figurative flag in the ground for what the company is about in the 21st century. It would cut utility costs by half, achieving 55 percent in water savings and 55 percent in energy savings compared with conventional Swedish buildings. But, as Skanska Project Manager Magnus Hellsten explains, there was more to it than that. “Entré Lindhagen demonstrates how Skanska walks the talk on green buildings. It is a showcase and inspiration for potential clients interested in green buildings that promote resource efficiency and realize significant financial savings.”

According to Skanska, Entré Lindhagen is, in effect, an exercise in marketing worth $180 million. Along with the energy and water figures, the headquarters comes with valuable marketing shorthand for its green credentials, having also achieved USGBC’s LEED Platinum Core & Shell certification – the highest attainable performance for a building’s design and construction. Thanks to LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) and the certification offered by BREEAM, which was established by the UK’s Building Research Establishment in 1990, sustainability has become quantifiable. Today, there are more than 40,000 commercial and institutional LEED-certified projects worldwide.

The LEED rating system was created by the USGBC almost two decades ago, to give businesses measurable tools for new construction. “For the past 20 years, the heart and soul behind USGBC has been our member organizations, of nearly 12,000, and their 13 million employees,” says the Council’s President and Chief Executive Officer Mahesh Ramanujam. “That network shares a steadfast belief that the green building movement has the power to change our world definitively for the better.”

None of this is conjecture; it is all supported by hard data. “If you take the real-asset sector, for example,” says Ramanujam, “investors, regulators, customers and other stakeholders are increasingly asking for greater transparency about the environmental, social and governance performance [ESG] of real asset portfolios.”

That demand has given rise to resources such as the Global ESG Benchmark for real assets, measured by GRESB, an Amsterdam-based investor-driven organization that assesses the ESG performance in an effort to enhance and protect shareholder value. According to Ramanujam, GRESB has more than 200 members globally, with more than $11 trillion in assets, and they are using GRESB’s data in their investment management and engagement process.

"Regulators are increasingly asking for greater transparency about the environmental, social and governance performance of real asset portfolios" – Mahesh Ramanujam, President and Chief Executive Officer, USGBC

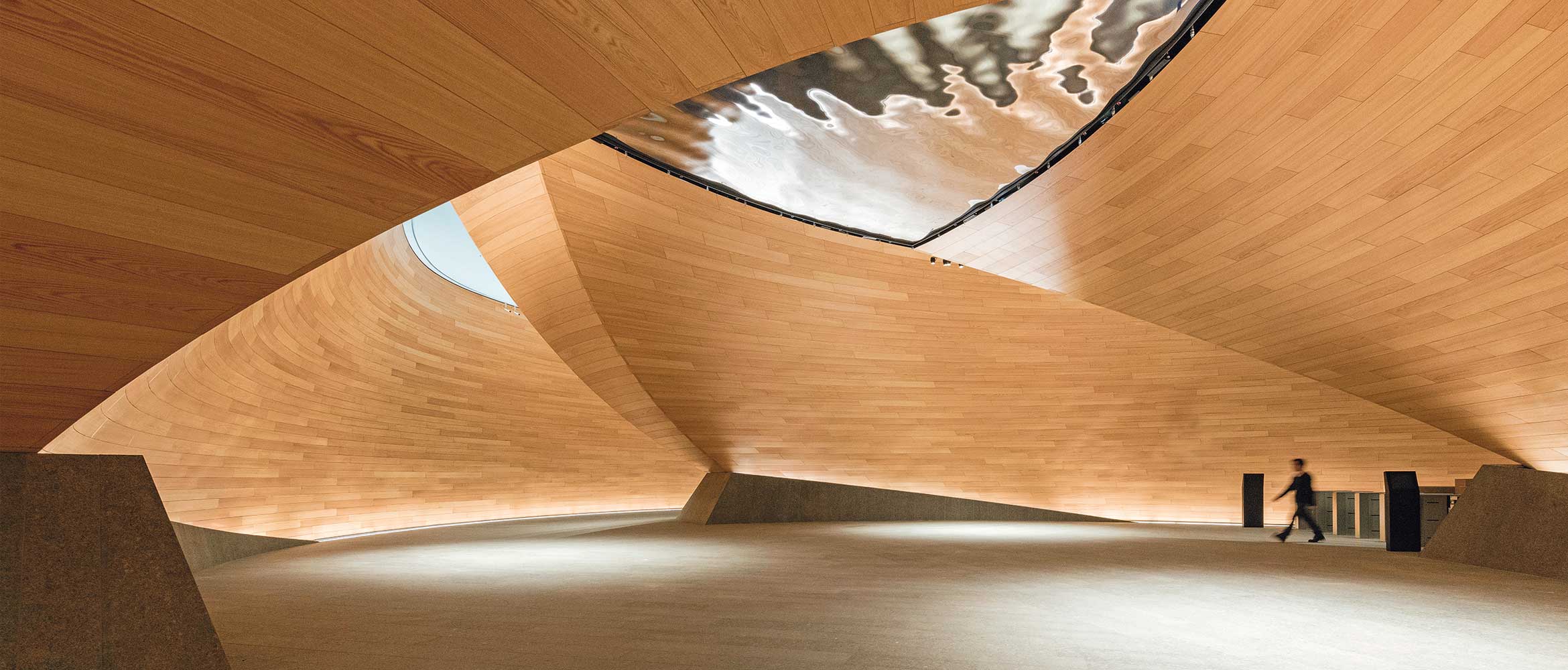

There are certain companies, however, with a broad international reach – in particular, those with an inherent and visible link to luxury and design – that inhabit historic architecture, designed long before sustainability and green technology were ever imaginable, let alone on any agenda. Watch brand Omega and its parent company Swatch Group, for example, have worked with the Japanese architect Shigeru Ban – often regarded as the king of green architecture – on a new headquarters in Biel, Switzerland, which opened in 2017. The main construction is made of timber, the only renewable building material in the world, but the development also incorporates several listed buildings belonging to Omega. These are almost impossible to retrofit to the LEED and BREEAM standards that new builds aim for today.

Likewise, when the French luxury group Kering moved to its new Paris headquarters, the former Laennec Hospital, in 2016, the building presented unique challenges. “It’s a historic building, dating back to the 18th century,” says Géraldine Vallejo, Kering’s Sustainability Program Director. “The changes we made were mostly in energy performance. We have real-time management of energy around the building and energy-efficient equipment. We achieved BREEAM and HQE [Haute Qualité Environnementale, the French equivalent of BREEAM], which had never been applied to a historic building before.”

The Kering headquarters is also innovating in other ways. “We are focused on wellbeing for the employees, which isn’t directly linked to the construction of the building,” adds Vallejo. “It’s about how people work. We have gardens with a beehive, a green wall, possibilities for people to work remotely and, once a month, someone comes in to give massages.”

Meanwhile, at the new Adobe offices in east London, created by design company Gensler, there are relaxation spaces and a mother’s room. Gensler’s designers have also created what they call “third spaces” to promote “serendipitous collisions” for communication and collaboration between groups. The building itself, the White Collar Factory, is LEED certified at the highest level, Platinum.

"The return on investments in improved workplace environments shows up in employee productivity and performance" – Rick Fedrizzi, Chairman and Chief Executive Officer, IWBI

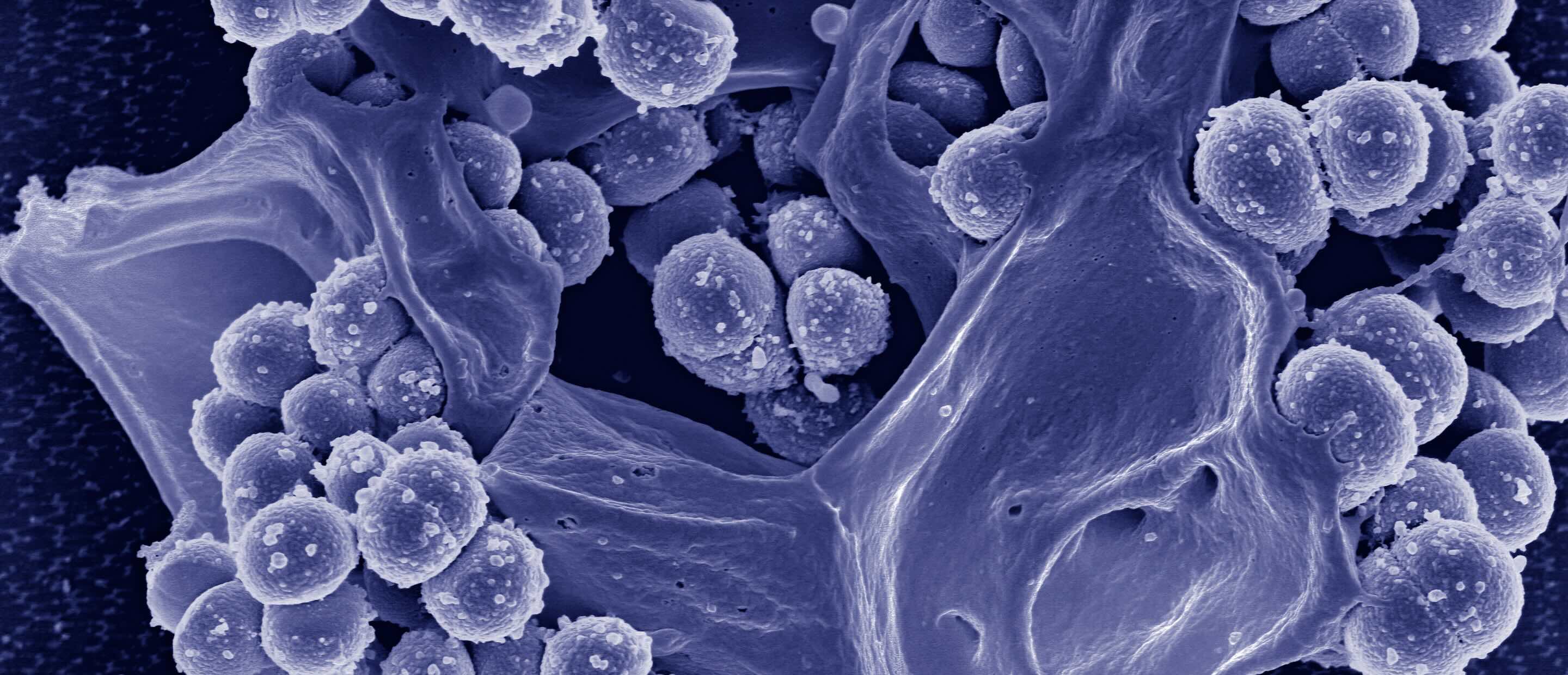

Wellbeing is often an objective in the construction of new buildings. The Skanska project focused on improvements in air flow. “The energy-efficient ventilation system created an even, indoor climate and a draught-free environment,” explains Hellsten. “Good air flow contributes to a decrease in sick leave and better performance at work.”

Just as a green approach to architecture is good for the environment, so a holistic approach to wellbeing for employees is good for day-to-day business. As with BREEAM, HQE and LEED, this factor is also being driven by highly organized initiatives. One of the most prominent was set by the IWBI in New York, which launched the WELL Building Standard in 2014, the first rating system to address human health and wellness in buildings.

“WELL is helping to facilitate what I like to call the ‘second wave of sustainability’ and transformation of the modern workplace,” explains the Institute’s Chairman and Chief Executive Officer, Rick Fedrizzi. “Approximately 90 percent of corporate expenses are tied to salary and benefits, which means the return on investments in improved workplace environments and cultures that encourage healthier behaviors shows up in employee productivity and performance. We’ve made such progress with building performance, it’s now time to focus on human performance and the contributions better buildings make towards helping humans thrive.”

WELL initiatives focus on a range of elements, from the quality of air to lighting, physical activity and food. But obtaining WELL Certification is a rigorous process – once a project is registered, it goes through rounds of assessment, documentation review and the process of performance verification. This involves onsite post-occupancy testing to ensure that theory at the design stage works in actuality. Since the launch of WELL in 2014, more than 750 projects are now registered or certified, suggesting a strong appetite in business globally for the initiative’s support and an alignment with it. In Europe, nearly 170 projects in 13 countries are included in that figure, and the movement is growing apace as the wellness aspect of a building is hardwired into its design.

PLP Architecture is working on the 22 Bishopsgate tower in the City of London, which is one of two dozen projects in the UK to be registered for WELL Certification. Elements that will be assessed upon the project’s completion include art and leisure, as well as a climbing wall and places for employees to take sleep breaks. “I think the sustainability debate has calmed down,” says PLP’s Bakker. “WELL standards are now the real subject of discussion, which is nice because it’s about people. It’s surprising to me that after a career of 25 years in creating buildings, it’s only now that the focus is on the experience of those working inside them.”

Crucially, in an age when financial and tech companies need to compete against one another to recruit the finest individuals in their field, potential star talent is looking closer at what each company can offer. And that is not just the best salary, or an interesting color scheme in a canteen with a playful layout and gaming pods. It is about serious life-enhancing aspects. Given that it is widely reported that we spend around 90 percent of our time inside buildings, it is this breath of fresh air to the design of work environments that is going to energize the companies of the future.

Mark C O’Flaherty is a writer who contributes to the Financial Times, the Telegraph and other major titles on design, travel and luxury lifestyle