Our CIO Special Report looks at the topic of biodiversity from a natural capital perspective, and provides insights into how we can start to tackle the “triple planetary crisis” around climate, nature and pollution. It includes a preface by Professor Sir Partha Dasgupta, Frank Ramsey Professor Emeritus of Economics, University of Cambridge.

The report discusses the conceptual framework provided by natural capital and the use of this to establish broad-based biodiversity objectives and measure progress towards them.

Topics covered include:

- Measuring biodiversity within the context of ESG

- Risk assessment of biodiversity

- The investment gap and transformation change required to close it

To download a PDF of the full report, please click here.

Introduction

Environmental concerns are likely to change the ways in which we assess the global economy. If a prime economic objective is to become more “nature neutral”, we may need to adopt different measures of success. A focus on the preservation of “natural capital” could complement traditional economic measures such as GDP. We look at the concept of natural capital in Chapter 3.

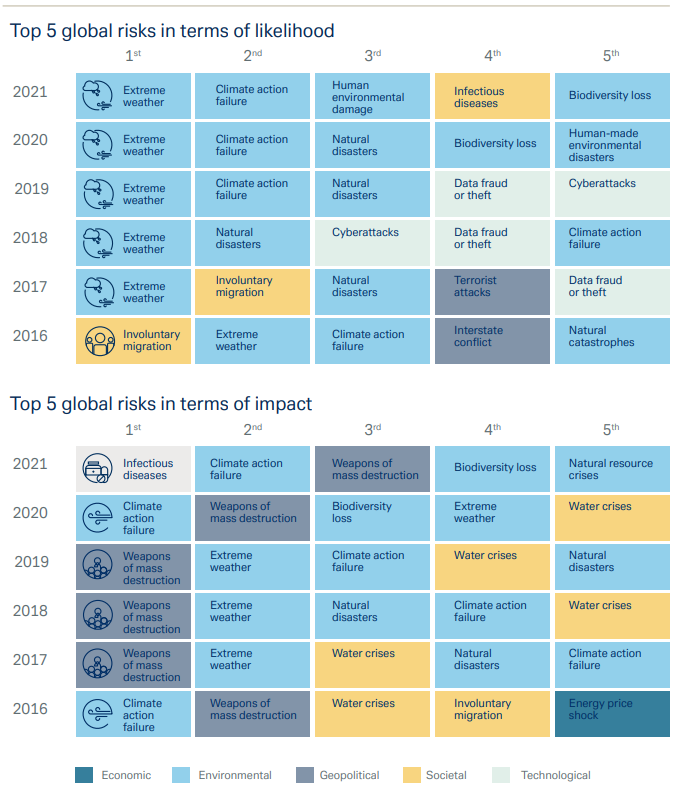

An alternative perspective on the importance of environmental issues and biodiversity loss can be gained by looking at the concept of specific risks, which we explore further in Chapter 4. It is important to realise that these risks may exist independently of individual companies’ ESG scores. In other words, simply investing on the basis of ESG scores does not eradicate these long-term risks.

In a nutshell: natural capital and biodiversity: measurement and investment

- The concept of natural capital is likely to become increasingly important in economic decision-making.

- Public investments have steadily increased, but by 2050 much more investment in natural capital will be required to preserve our natural world while successfully managing the associated triple planetary crisis.

- Hence, a natural capital framework should help us make and measure progress on biodiversity within existing broad-based objectives.

- In addition, the dynamics of transformation processes (e.g. “system leaps”), which focus on the need to identify guiding principles and the likelihood that “intermediary” transitions may be more complex than end-goal transitions, can effect economic and social change in a short time.

The concept of natural capital

In previous periods of economic change, the environmental dimension was usually ignored. But, this time around, there is a growing understanding that environmental threats will undermine the well-being and prosperity of present and future generations if not tackled properly.

Rather than focusing simply on economic growth, or the relocation of resources across sectors, we are likely to focus more and more on economic sustainability.

Hence, the concept of natural capital (natural assets such as water, soil, air, and all living things) is likely to become increasingly important in economic decision-making. This increase in interest in natural capital will go hand-in-hand with a growing emphasis on biodiversity.

Measuring biodiversity in an ESG context

Biodiversity is already on investors’ radar, but it still receives less recognition than other environmental issues. This is evident from investor patterns and surveys. For example, in our recently conducted survey on biodiversity, only 11% put biodiversity in the top spot for environmental issues. Around 37% see ocean as well as land degradation as equally important and 46% of investors regard climate change as the most important factor.

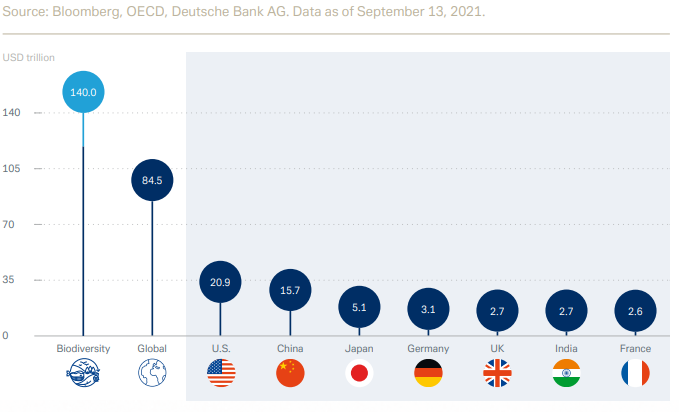

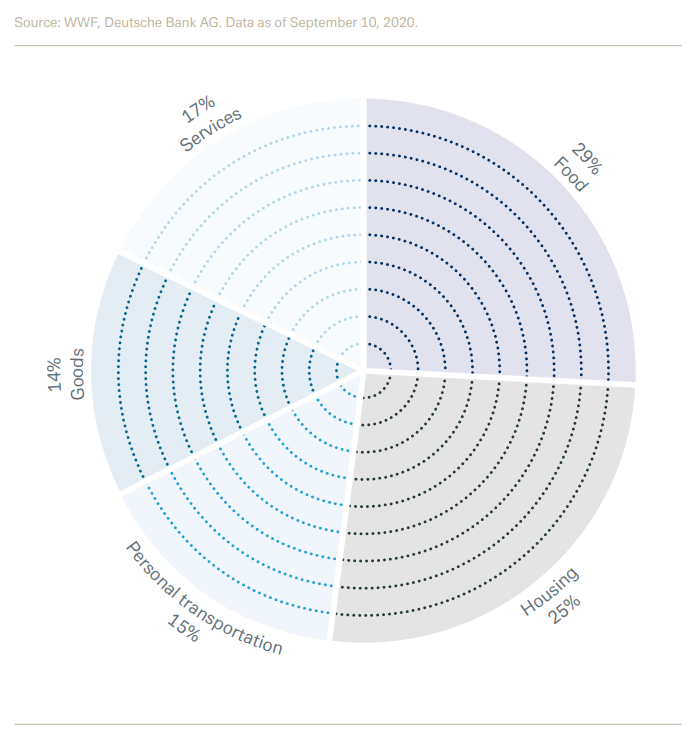

There are various ways of measuring human impact on biodiversity. One of these is the ecological footprint. This measures how much demand human consumption places on biodiversity and can be compared to the sustainable biodiversity capacity (biocapacity). According to one estimate, the overall ecological footprint amounted to 2.6 global hectares per person in 2020, whereby the biocapacity was only around 1.6.11 In other words, we are creating long-term risks by jeopardising biodiversity and depleting natural capital. Figure 4 estimates humanity’s ecological footprint by type of activity.

Biodiversity risk assessment

Figure 5 provides one assessment, looking at the top five risks in terms of both likelihood and impact and how this has changed over time according to the World Economic Forum's Global Risks Report, which is published annually and describes changes occurring in the global risks landscape. Here, environmental risks such as biodiversity loss, natural resource crises and climate action failure dominate and represent the greatest risks.

Closing the investment gap

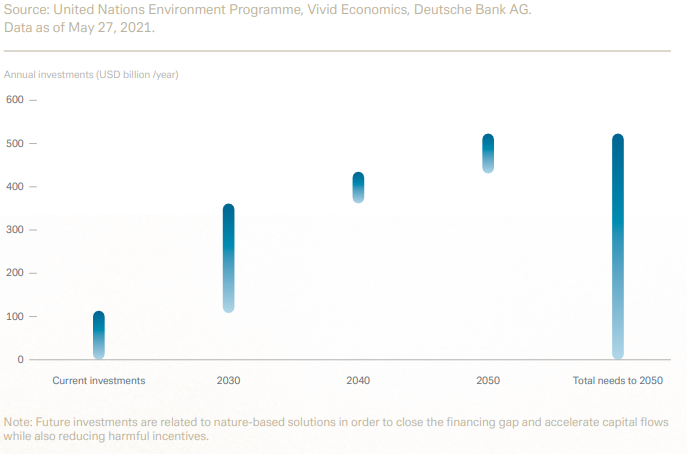

Data shows that public investments in biodiversity have increased steadily since 2008 and currently represent 0.19-0.25% of global GDP.18 Nonetheless, it is calculated (by the United Nations Environment Programme) that USD8.1 trillion of investments in natural capital are required between now and 2050 in order to sustain our natural world and at the same time successfully tackle the interlinked triple planetary crisis. The finance gap stands at USD4.1 trillion between now and 2050, and the annual investment that would be required for structural transformation (technological advancement and innovation) could reach USD536 billion by 2050, reflecting a four-fold increase from current investments (capital flows towards sustainable practises) of USD133 billion (2020) as shown in Figure 7.19 As an example, forest-based solutions alone, including the management, conservation and restoration of forests, will require alone around USD200 billion in total annual expenditure globally.

The change process

Investment principles and biodiversity. Protection efforts will become a more integral part of the investment in our natural capital. Currently, only 17% of land and 7% of seas fall under some sort of protection.23 International and multilateral organisations already play a major role in connecting public and private sectors in efforts to deploy biodiversity investments. For example, the Principles for Responsible Banking (PRB) were developed by the banking industry in collaboration with the United Nations Environment Programme Finance Initiative (UNEP FI).

However, biodiversity may still not be getting the focus it needs. Of the 252 total signatories to the PRB, just 24 identified biodiversity as a significant impact area, and a further six noted it as an impact area. This is significantly lower than other themes, for example climate change mitigation (152 and 10), financial inclusion (87 and 8) and human rights (36 and 10). Of the 30 signatories who cited biodiversity as an impact area, one-third to one-half have policies related to different aspects of biodiversity in place, on key themes

To download a PDF of the full report, please click here.

.webp)