Impact #3: The political economy – seeing in 4D

• Monetary policy magic prolonged? • Inflation and other potential policy threats • Fiscal policy under pressure • Debt escalation

So, from the perspectives of individuals and companies, this will not be a return to a pre-coronavirus world. Governments are well aware of this and must manage most medium-term problems around transition and long-term recovery issues.

As noted, we think that 4Ds – divergence, digitalisation, demographics and debt – will characterise many aspects of the post-COVID world. These 4Ds will come into even greater prominence when you consider future trends in the “political economy” – i.e. when you broaden out economic considerations to bring in social, political and institutional issues.

Result #1: Monetary policy magic prolonged?

The title of our annual outlook last year was "The end of monetary magic?". Our answer to the question was "no", because we believed that although its efficacy might be fading, it remained a crucial policy tool - particularly if supported by fiscal policy. Faced by an extreme situation resulting from the coronavirus pandemic, policymakers dug even deeper into their monetary magic toolboxes in 2020. This was done not only through keeping rates low and monetary authorities’ balance sheets large, but also through other interventions in financial markets (for example corporate bonds).

Despite continued worries about the possibly fading power of each additional increment of monetary policy easing, a replacement has yet to be found (despite a general agreement that complementary approaches, e.g. fiscal policy, structural reforms and so on, need to be developed further). A year ago, it was clear that many of the factors hurting economic performance were non-monetary in nature and thus beyond the scope of monetary policy to address or ameliorate: this remains the case and effort still needs to be put into alternative policy approaches. As we discuss in Result #3, fiscal policy will become important in 2021.

Result #2: ESG – onwards and upwards

The immediate threats to monetary policy seem containable. Political consensus is still for highly accommodative monetary policy and the consequence will be low yields for even longer, maintaining the hunt for yield.

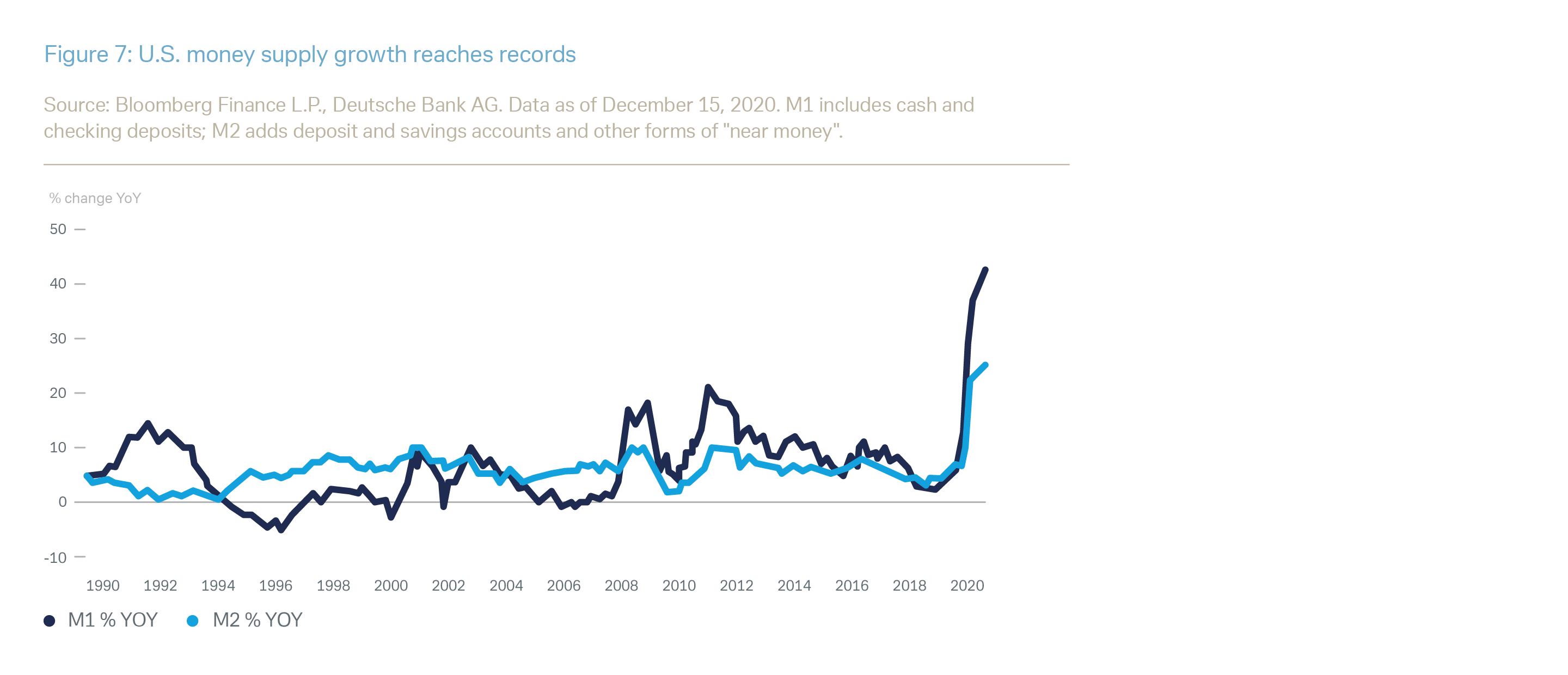

We would not be completely relaxed about inflation, however, and this is a potential threat to monetary policy. The immediate threat from inflation at present appears low, given continued spare capacity and still cautious consumers in many markets (driven in part by continuing fears around unemployment). Our forecasts reflect this. But while much attention has been paid to the “Japanification” story (i.e. low growth, low inflation) this is not necessarily how developments will unfold. Concerns remain about high monetary aggregates for example, and an upward spike in yields cannot be ruled out. Changes in the operating model for services companies (given the difficulties around revenue generation in a still rather socially-distanced environment) may also increase upwards price pressures. There are also broader worries about the possible longer-term implications of deglobalisation or regionalisation on price levels.

Other long-term threats to monetary policy remain too. Monetary policy is essentially a blunt instrument and cannot easily deal with issues of divergence within economies or between them (indeed, accommodative monetary policy may make social inequality worse through inflating the value of certain assets). Monetary policy will also run up against structural problems in economies, perhaps caused by demographics (perhaps tending to push up savings, irrespective of accommodative policy) or rapidly escalating levels of debt (see Result #4). Expect discussion on these issues to intensify the longer the unconventional measures remain in place.

The remaining “D” – digitalisation – could be both a threat and an opportunity for monetary policy. Further testing (e.g. via regional schemes already in place within China) and rollouts of central bank digital currencies (CBDC) around the world offer the prospect of much more targeted monetary/fiscal policy – for example, through time-limited and spending-directed transfers. This targeting – particularly if it has a time-limited component – may eventually offer a way out of the so-called “liquidity trap”, when low or negative rates reduce the effectiveness of monetary policy through removing the disincentive to hold cash. But continuing uncertainties around the operation of CBDCs must also present risks to monetary policy overall, and the political implications of targeting might also end up eroding the independence of central banks – as some would like.

Result #3: Tech still has a role to play

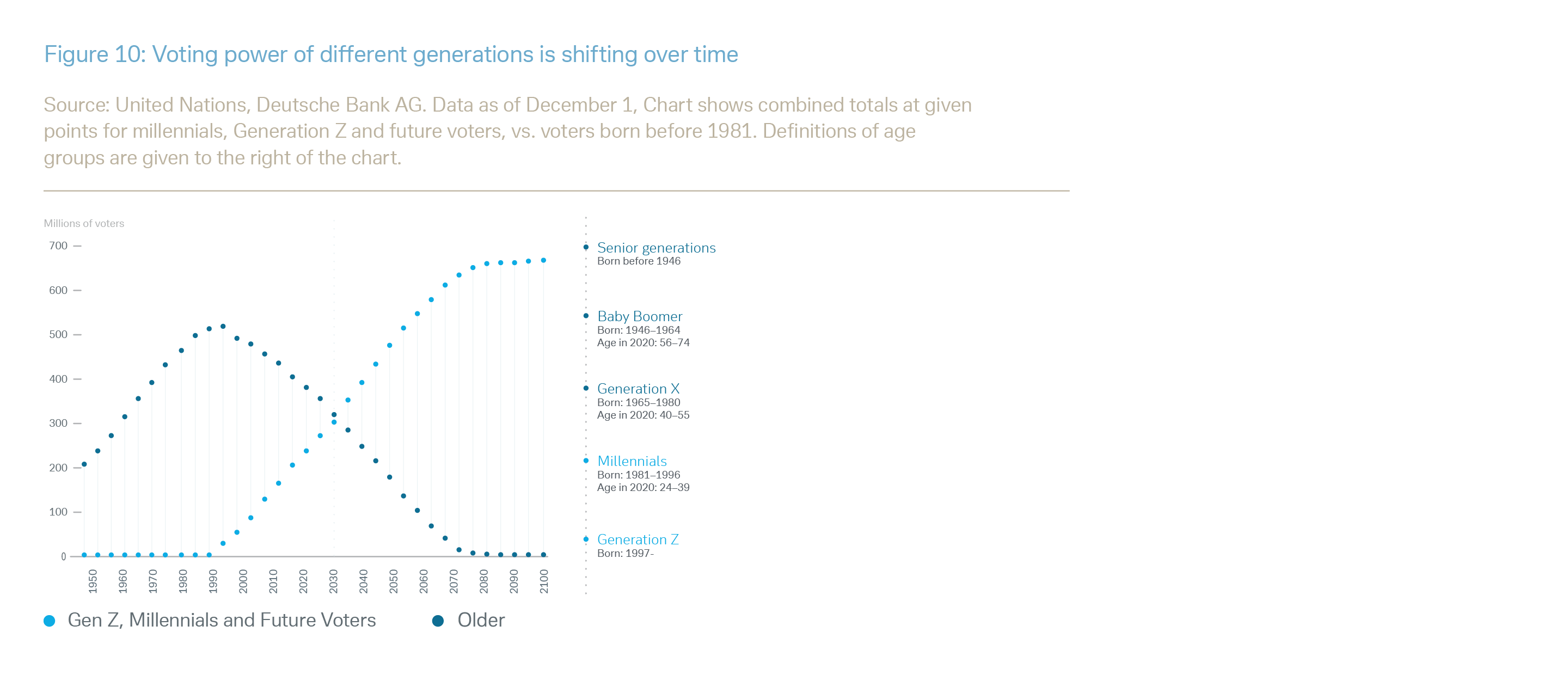

Fiscal policy is overtly political in a way that monetary policy has not been in most developed market economies since the 1990s. This politicisation of fiscal policy has a number of implications. First, policy can be subject to a swing in overall sentiment – the general acceptance of massive fiscal stimulus in 2020 on a “needs must” basis may not be sustained for ever, although it is generally much more difficult to screw back the fiscal policy tap than to open it. Second, fiscal policy can get caught up in separate political debates (as did, in late 2020, the fiscal support package in the U.S. and the European Recovery Fund). Third, fiscal policy will have to be seen as directly addressing divergence problems in society, with demographic changes both having an impact on the need for it and also the strength of political voices in play – including those of millennials (a key theme). Healthcare may remain a priority for fiscal spending but infrastructure (also a key theme) will also demand attention.

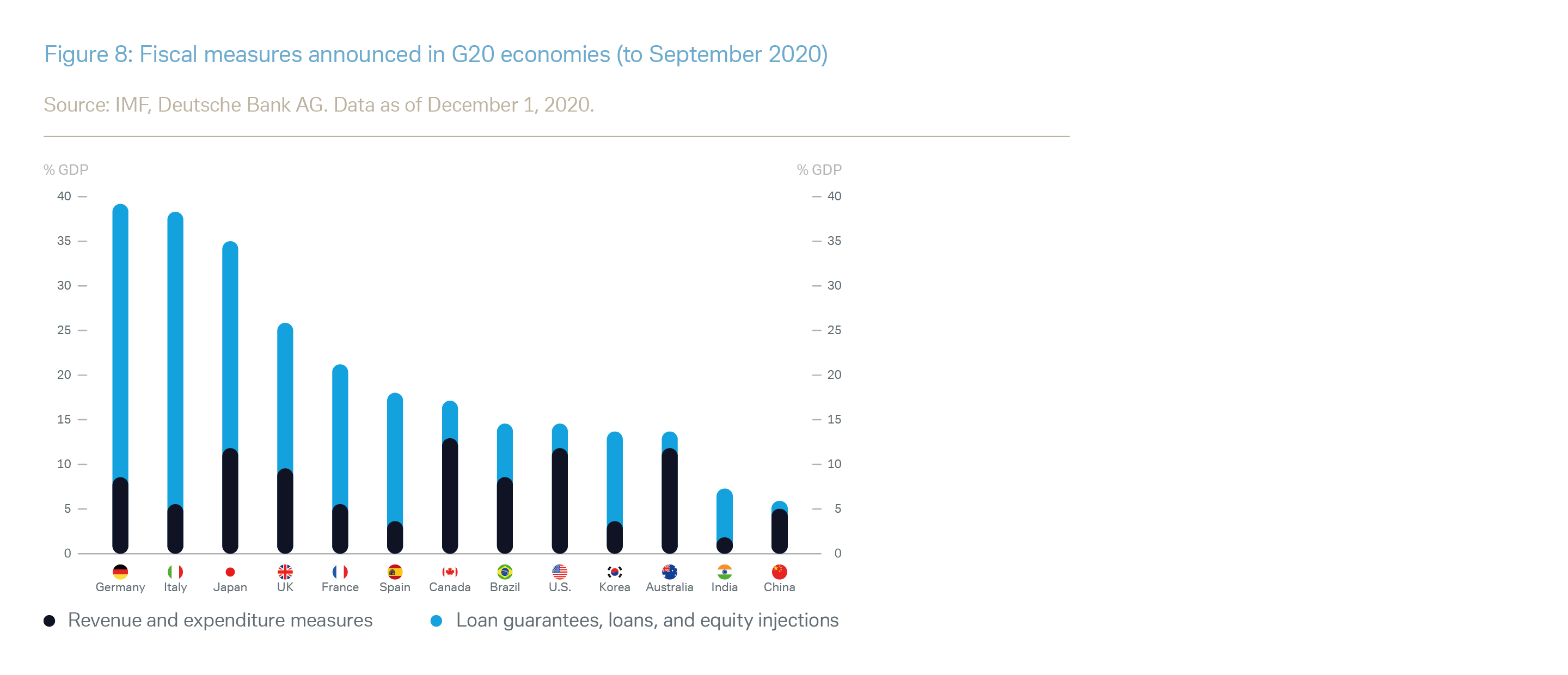

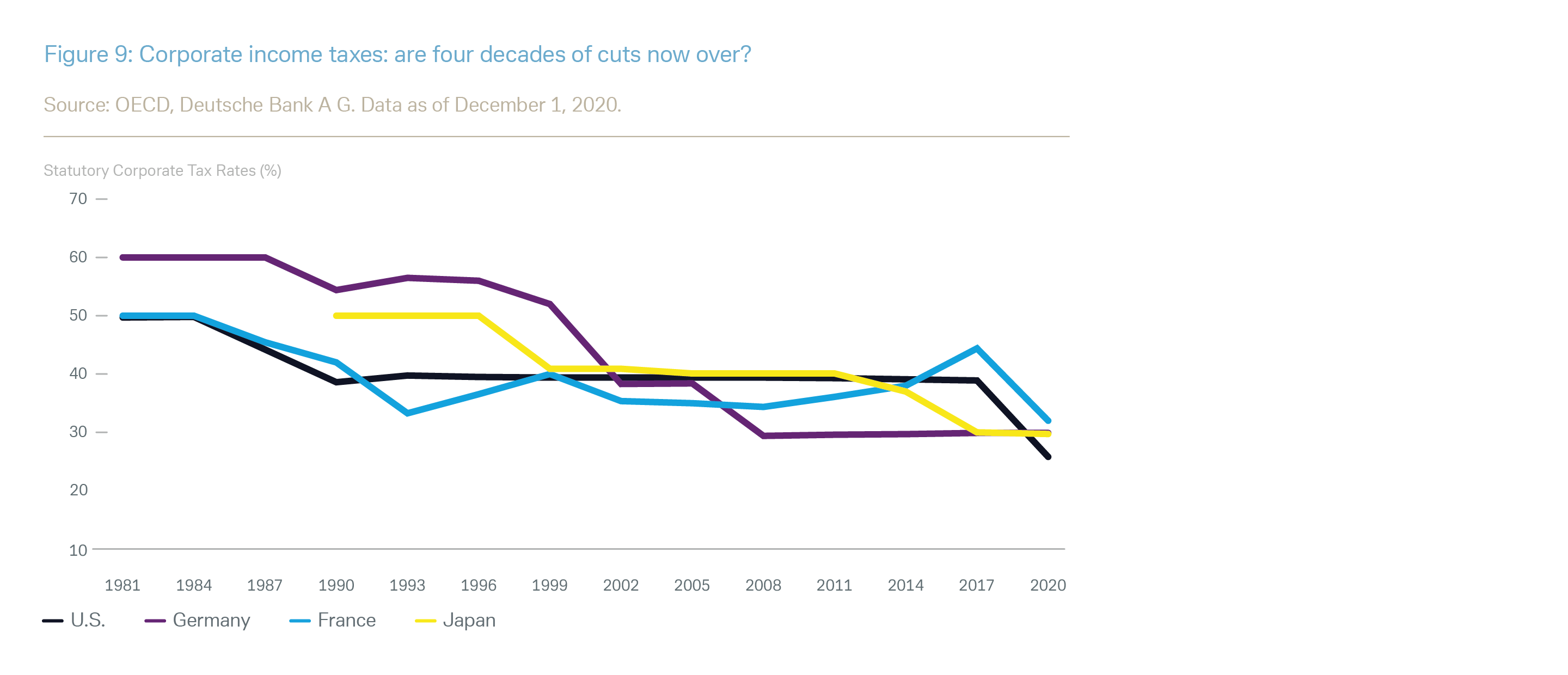

However these political debates play out, it is difficult to see a situation where we don’t see some increase in taxation, given the extent of fiscal measures unveiled in 2020 (Figure 8). In particular, the race to the bottom on corporate taxation – evident since the early 1980s (Figure 9) – may now be coming to an end. Finance ministers around the world will be battling a number of competing priorities: fiscal policy will be operating under great pressure and, as noted above, at a time when the composition of the electorates that ultimately control it is also shifting (Figure 10). There will be continued calls for higher taxes on those perceived as being relatively less affected by the crisis (i.e. higher income earners and the wealthy) – in particular as the latter group may be seen as benefiting from loose monetary policy through rising real asset values. It is quite possible that we shall see rises in taxes, not just on corporates but also on wealthier citizens to deal with perceived inequalities as well as finance increased budget deficits.

Result #4: Debt escalation

Expansionary fiscal policy and escalating budget deficits have exacerbated an existing trend – as we have discussed in a previous report (“Peak debt: sustainability and investment implications" published in 2019).

Where does this all leave fixed income as an asset class? Rising levels of debt have not so far unsettled the financial markets – there are still willing buyers for government debt – but worries could increase. There will be several reasons for this. Debt taken on in 2020 to deal with coronavirus downturns was in effect replacing lost income – it has not being spent in the hope of stimulating faster growth, as per the Keynesian prescription. And hopes that economies could grow their way out of debt – the usual route – could be stymied by worries about tightening fiscal policies and lack of productivity improvements, until the benefits from tech-related investments (e.g. artificial intelligence and 5G, two of our key themes) start feeding through. It also seems unlikely that inflation will provide much relief. Meanwhile, countries may be facing increasing demographic pressures (as has Japan) increasing debt levels yet further. Eventually markets will get concerned, and the possibility of a spike in government yields during 2021 is a real one, even though the long-term outlook for yields remains lower for even longer, with multiple consequences for all asset classes. Financial repression (i.e. negative real yields) will be a notable consequence.

Consequences

- Monetary magic continues, fiscal policy complements.

- Financial repression.

- Higher debt leads to a new tax debate.

Our full CIO Insights report “Annual Outlook 2021: Tectonic shifts" includes our new macroeconomic and financial market forecasts for 2021. Please refer to the Important Notes at the end of the report for disclosures and risk warnings.

To download a printer-friendly PDF of the full report, please click here.

To view a mobile-optimised version of the full report, please click here.